Knock Fell Caverns is a unique trip for the caver who fancies something a bit different than the typical Yorkshire Dales stream cave. Located under the summit of Knock Fell, which is conveniently accessed from the A66 at Appleby-in-Westmorland, the cave presents a hugely varied series of interconnected passages running in a broadly north-south and east-west direction. Wikipedia states that the cave is the “most extensive maze cave system in Britain” and the navigational challenges within are not to be underestimated. The total length of the system is around 4.5 kilometres.

The publicly available survey (also available without annotations) highlights the complexity of the cave. What the survey does not show, however, is the huge variety of passage located within the system. This is a cave that has almost everything; most trips into the cave will encompass tight squeezes, as well as generously sized chambers, beautiful formations, unpleasant muddy crawls, impressively tall rifts, leisurely walking passage, boulder chokes, and (of course) testing navigation.

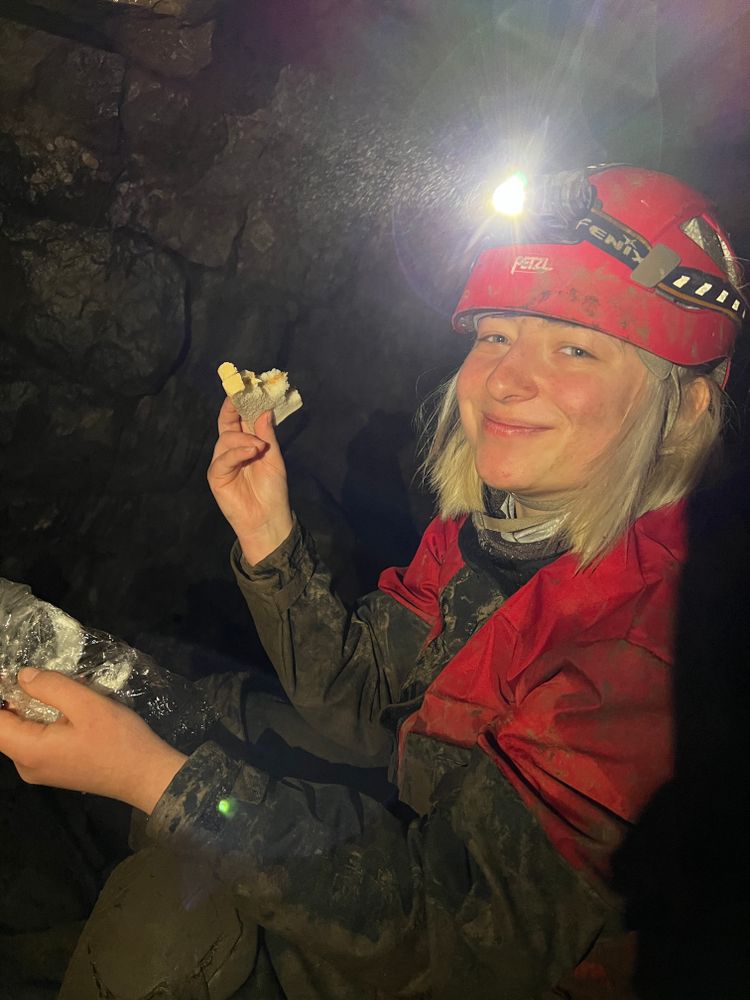

Gracie and I, when visiting on 19th February 2022, got the impression that the cave does not receive a lot of traffic. Perhaps this is due to the location outside the main Yorkshire Dales caving area, or the intimidating complexity - either way, it seems a shame! Many of the passages within looked as if they had barely visited (even on the main ‘trade route’ marked on the annotated survey). The impressive, orange-tinted formations located throughout the system were very well-preserved.

Access to the cave is by way of a private road which was built to facilitate the construction of the radar station which sits atop Great Dun Fell. The road is not on many navigation devices, although it is exceptionally well surfaced. Parking at a lay-by near the top gives immediate access to the Pennine Way which can be followed for around 600 metres to get to the cave in ten minutes or less. The lay-by provides space for just one vehicle (or maybe not even that, if you have a big car), but there are several of them along the distance of the road and space for a couple or three cars together right at the top near the radar station gate.

The views from this area (above) are spectacular and it is well worth a visit even if you are not intending to go underground. A northbound walk along the Pennine Way leads across to Cross Fell which is the highest point in England outside of the Lake District at 893 metres. The single-track road is very steep (and therefore popular with masochistic cyclists) and great care would need to be taken in wintry conditions.

The entrance is on access land and was not locked when we visited, although the CNCC website lists details of Natural England who request you email them before your trip.Users on UKCaving have pointed out that the road may be in regular use by HGVs for access to the radar station and Silverband Mine. With this in mind, it would be prudent and polite to ensure that any parking gives due consideration to large vehicles that may be trying to traverse one of the sharp bends on the road. If you are in any doubt whether an HGV can clear your parked vehicle, it would be best to make your way to the top of the road where more space is available or avoid parking on the road at all. It would be unwise to cause issues that may inhibit access to this area in future; walking to the cave without the use of this road would take at least two hours (it is over 6 km and 600m elevation) and be prohibitive for most sporting trips.

The entrance to the cave is a gated vertical shaft located in a group of deep shakeholes. GPS is strongly recommended to help locate the entrance! The ‘lid’ required quite a lot of persuasion to open and initially we were concerned we might be unable to do so - thankfully brute force and ignorance eventually prevailed. No permit is required to descend the system, as it is on access land, however the CNCC website states that Natural England request cavers seek authority to attend via email. In our case, the trip was planned at the last minute, and we did not have time to do so.

No SRT is required to enter the cave and the entrance climb down (8 metres) is quite straightforward even for the vertically challenged. We rigged a handline however this was not used for anything other than hauling the bag in and out.

A compass is absolutely essential on this trip and is required as soon as you reach the bottom of the entrance shaft. Two ways on are presented, with one being a tight connection towards the north end of the system and the more popular southern route leading to a relatively unpleasant, but short, rocky crawl towards the impressive Scotch Corner Chamber. Scotch Corner marks the beginning of a round trip which is suggested as a ‘typical route’ on the survey, which we followed in an anticlockwise direction.

The cave contains a mixture of crawling, walking, stooping and tall rift traversing.We found the survey to be extremely accurate in the sections of cave that we visited, and our laminated copy never left our hands. The compass and survey allowed us to always be quite sure of our location, with one exception - detailed later. I cannot empathise enough how easy it would be to get dangerously lost within this system. A lot of the passages can look very similar and a constant awareness of your position, both generally and within the current passage, is required. We found ourselves backtracking occasionally to count the junctions we had passed, to ensure we took the correct turn. When we visit again, we will take a permanent marker to mark off our progress on the survey as we travel, as it was quite some effort to try and concentrate on maintaining our location in our heads without becoming distracted by chatting or crawling.

I have seen tales online of an old tape marker system which once existed within this cave. We did see some remnants of this - the odd bit of tape was laid on a rock at a junction, or perhaps one was seen to have fallen between some rocks on the floor, but it did not seem to produce any coherent navigation system and should not be relied upon. Some arrows had also been drawn on walls in certain locations, but it was not always clear what they were pointing to (one would assume out, but it didn’t always make sense that this would be the case).

No route description exists that I am aware of (although I welcome corrections). If it did, it would be extremely hard to follow (turn right, then pass three lefts, then turn left, then take the second right…), and likely not in the ‘spirit’ of this sort of cave. We managed quite well with just the survey and a compass, even though it was the first time we had attempted this type of navigation underground.

A fault formed hypogenic passage with formations, typical of that within the Knock Fell Caverns system.Whilst a good portion of the cave is pleasant walking passage, there are regular crawling sections and some parts that could reasonably be described as a squeeze. This seemed more prevalent in the southern and eastern sections of the cave, with the passage back to the entrance via the central area of the cave and the Trans-Pennine Passage being quite large chambers indeed. The benefit of having a route description is that one can expect that the next turn may be unpleasant - with just a survey and compass, we found ourselves staring at some junctions and wondering “Can the way on really be down there? Surely it’s not that?”. Often it was.

Knock Fell Caverns is a hypogenic maze cave, which means that it was not formed by way of an active stream, as with most British caves. Caves and Karst of the Yorkshire Dales (BCRA, 2013) states that Knock Fell was likely formed by way of slow moving water from adjacent aquifers, at a time when the water table was raised. This water was forced along the north-south and east-west aligned faults over many years to produce the layout that is present today.

Some of the larger chambers in the cave may have been formed by way of rock collapse at the intersections of these fault-aligned passages. The CNCC website displays a warning (published in 2015) of recent collapse within the system. Several of the boulders we encountered looked remarkably fresh and had a large amount of undisturbed dust and rock around them, even on well trafficked routes. While it would be impossible for me to say whether this was fresh collapse or not, it certainly seemed likely.

One of the several larger chambers found in between the maze of interconnected passages.The most notable implication of the way this system was formed is that there is very little water within the cave and no streamway to speak of. The passages within the system do not exhibit the typical remnants of active streamway development, such as scalloped walls. There are a few drippy avens, including one which has formed an impressively deep hole near Scotch Corner Chamber. We visited at the tail-end of Storm Eunice and the cave was remarkably dry.

The only stressful navigational moment during our visit was in the central section of the cave. We were progressing northwards and expecting to find a left turn at the end of the passage, as per the survey, but instead found a completely choked route when we arrived there. I thought that I had been very carefully monitoring our progress and position, but clearly something had gone wrong. Realising that I did not know where we were, I totally lost faith in my navigation at this point and decided that a complete re-evaluation was required.

It was not overly helpful, although unavoidable, that some of the passages sketched in the survey look almost identical those adjacent to them. After failing to locate our position again through referencing the drawings on the survey, I set off to explore the immediately adjacent passages to see if there were any clues. Once I found Myotis Chamber and the nearby ‘double-pronged’ passage two junctions to the east of it, I was once again totally confident in our position. This whole incident took around thirty minutes to sort out and I was very grateful when it was resolved. In the end, we were only about 10 metres from where we thought we were.

The journey out from this point was quite straightforward, barring a couple of ambiguous routes that were available just north of Trans-Pennine Passage. Luckily, we got the right route on the first attempt through this area, by pure chance.

The whole trip took around five hours, and we are both very keen to go back at some point and explore the countless passages that we did not manage to visit. I would be surprised if we traversed much more than 10% of the system on our initial trip. Knock Fell Caverns provided one of the most interesting sporting trips that I have done so far in my short caving career, and I would strongly recommend it to anyone who is yet to visit.

Update 25/02/2022: A paragraph was added advising caution regarding parking on the access road, following feedback from users on UKCaving.